How Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Supports Wound Healing and Tissue Repair

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is one of the body’s hidden heroes when it comes to healing.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is one of the body’s hidden heroes when it comes to healing. It plays a major role in helping wounds close and damaged tissues rebuild themselves. This isn’t just a scientific fact—it has real-world importance. The global advanced wound care market is expected to reach around 19 billion dollars by 2027, showing how essential it is to understand how our bodies repair themselves. And with serious conditions like pulmonary fibrosis affecting 1 in every 5000 people, it’s clear that when healing goes wrong, it can become a big health problem.

Whenever the skin or any other tissue gets injured, the body immediately activates a fascinating repair system. Since the skin is our first line of defense against the outside world, the body has developed complex ways to protect and fix it. During this process, the extracellular matrix acts like a temporary scaffold, filling in the damaged area and giving structure to the new tissue that will form.

This healing process isn’t done by one cell alone—it’s a team effort. Platelets, neutrophils, macrophages, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and keratinocytes all join in. The ECM helps guide these cells to do their jobs. Among them, fibroblasts are key players. They develop from basic (undifferentiated) mesenchymal cells when growth factors—chemical signals released by other cells—tell them it’s time to step in and start building.

But healing doesn’t always go smoothly. Sometimes, the body stays stuck in a state of chronic inflammation, which can stop proper repair from happening. This may result in too much scar tissue (fibrosis) or wounds that simply won’t heal. That’s why understanding how the extracellular matrix supports tissue repair is so important—it helps scientists and doctors develop better treatments for people struggling with these problems.

ECM Unveiled: Structure, Function, and Its Role in Repair

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is the structural and biochemical backbone of all tissues in the body. Far from being an inert scaffold, it is a highly dynamic, three-dimensional network composed of more than 300 macromolecules that surround and support cells [1].

It not only provides physical structure but also regulates cell behavior, guiding processes such as cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, and survival. In tissue repair, the ECM acts as a central command center—coordinating signals between cells and shaping the entire healing response.

What Exactly is The Extracellular Matrix?

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is the part of our tissues and organs that isn’t made up of cells. You can think of it as the “background framework” that holds everything together. But it’s far from just a static structure — it’s actually a dynamic and living network made of proteins and carbohydrates that gives cells the support they need to stay organized, communicate, and repair themselves.

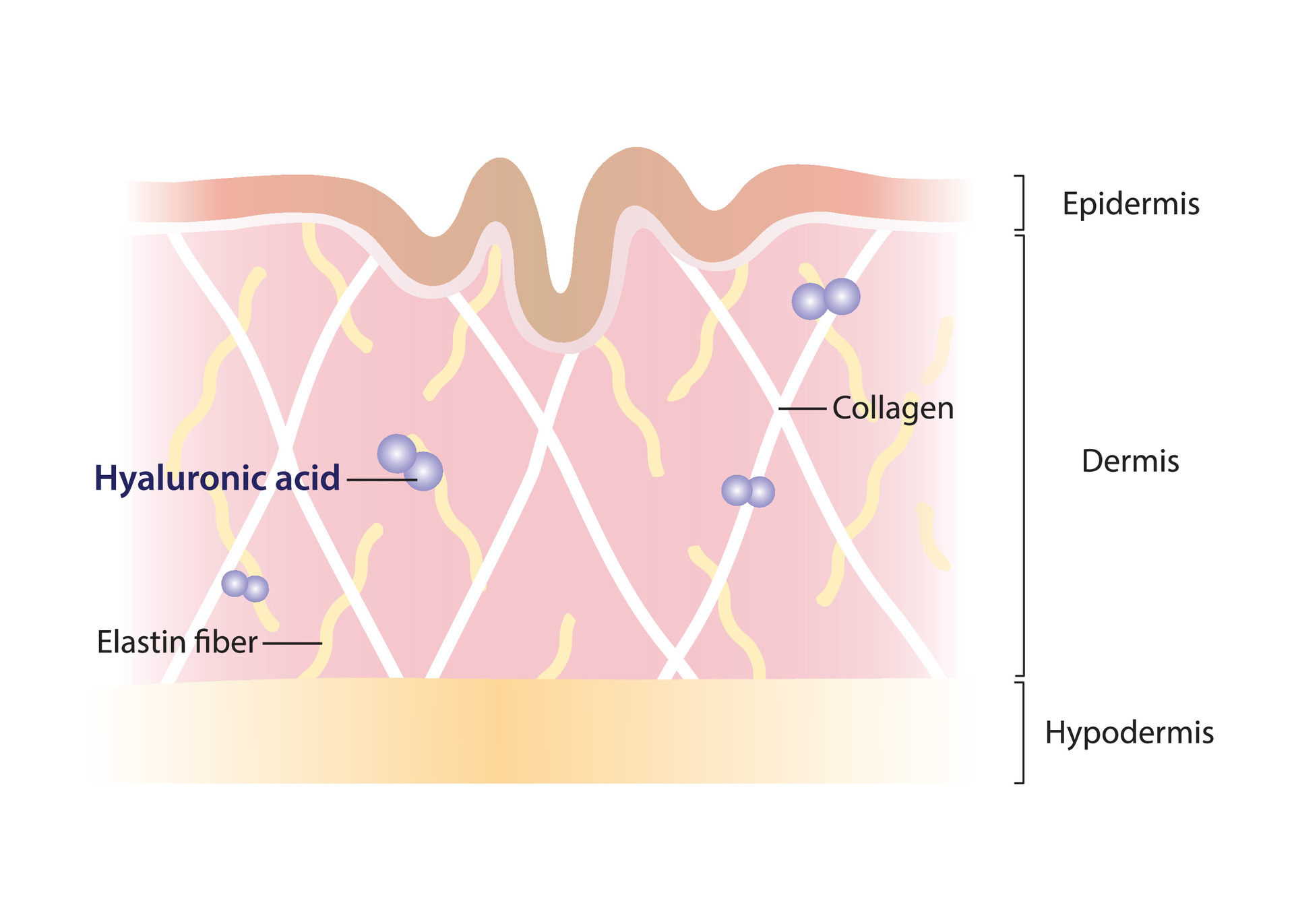

This amazing network has several key building blocks:

- Collagens: The most common protein in the body — made by fibroblasts — and found in 27 different types. Collagen gives strength and structure to tissues, much like the steel bars inside concrete.

- Proteoglycans: These have a bottle-brush shape made of both proteins and sugars. They attract water, helping tissues stay hydrated and soft, acting like natural shock absorbers.

- Fibronectin and Laminin: These are glycoproteins that form connections between cells and the matrix — imagine them as bridges or glue that hold everything in place.

- Elastin: This gives tissues their stretch and bounce, helping skin, lungs, and blood vessels return to their normal shape after movement or pressure.

How the Extracellular Matrix Connects and Communicates with Cells

The extracellular matrix (ECM) doesn’t just sit around holding cells in place—it also helps them talk to each other and stay connected. This happens through special proteins on the surface of cells called integrins. These integrins act like tiny anchors, linking the outside world (the ECM) to the inside of the cell, specifically to the cell’s internal skeleton.

But the ECM does more than just connect—it also helps create a two-way communication system between cells and their surroundings.

- Outside-in signaling: This happens when proteins in the ECM attach to integrins on the cell surface. This sends messages into the cell, telling it how to behave—like when to grow, move, or repair.

- Inside-out signaling: Here, the message starts inside the cell. The cell sends signals that change how integrins work, which affects how strongly the cell attaches to the ECM or reacts to it.

In simple terms, the ECM and cells are constantly talking back and forth, making sure tissues stay strong, connected, and able to heal when injured.

Mechanical and Biochemical Roles of the ECM

The extracellular matrix (ECM) has two important jobs in the body: supporting tissues physically and guiding them chemically.

1. Mechanical Support – The Body’s Natural Framework

The ECM gives tissues their shape, strength, and stability. But not all tissues are the same—some are soft, others are very firm. That’s because the stiffness of the ECM varies depending on where it is in the body.

In soft tissues like fat or the brain, the ECM is very gentle—only a few hundred pascals.

- In soft tissues like fat or the brain, the ECM is very gentle—only a few hundred pascals.

- In hard tissues like bone, it becomes extremely stiff—reaching gigapascals.

This structural support helps organs stay in place and allows cells to grow in the right direction.

2. Biochemical Support – A Storage and Signaling Center

The ECM is also like a storage bank for growth factors—special molecules that tell cells when to divide, repair, or rest. By controlling when and how these growth factors are released, the ECM helps regulate cell growth, wound healing, and overall balance in the body (homeostasis).

A key part of this system is proteoglycans. These molecules can hold onto growth factors, acting like:

- Co-receptors (helping cells receive signals), or

- Signal presenters (delivering messages between cells).

By combining physical strength and biochemical control, the ECM guides how tissues form, how cells behave, and how the body heals after injury. It's like an invisible conductor, quietly organizing the entire healing process.

How the ECM Works with Cells During Healing

When a wound occurs, the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the surrounding cells don’t just sit and wait—they communicate and work together to repair the damage. This creates a two-way conversation between cells and the ECM.

The ECM doesn’t only support cells physically—it also sends signals that guide what cells should do, such as when to move, divide, or start building new tissue. At the same time, cells can change the ECM, shaping it to fit the needs of the healing area.

This constant back-and-forth interaction helps organize the repair process and plays a major role in whether a wound heals properly or not.

Cell Adhesion and Migration: How Cells Move to Heal Wounds

For healing to begin, cells first need to stick to the extracellular matrix (ECM). They do this using special surface proteins called integrins—you can think of them as the cell’s tiny “hands” that grab onto the matrix.

One of the most important healing cells is the fibroblast. These cells don’t just attach randomly—they follow a specific order:

- First, they attach to fibronectin

- Then to vitronectin

- Finally, they connect to collagen

This step-by-step process helps create tension in the tissue, which is essential for pulling the wound edges together and closing the wound.

💡How the ECM Guides Cells to the Right Place

The ECM isn’t just a surface to hold onto—it also acts like a navigation system, guiding cells to where they’re needed.

- In developing tissues, neural crest cells can reshape messy fibronectin into long, organized tracks, which then act like highways for other cells to follow.

- In places like breast tissue, collagen fibers are already arranged in specific patterns, and cells use these as pre-built pathways to move along.

This kind of physical guidance is crucial, because without it, cells wouldn’t know where to go, and healing would be slow or disorganized.

Growth Factor Signaling and the ECM

The extracellular matrix (ECM) isn’t just a physical support system—it also plays an active role in controlling and speeding up healing by managing growth factors.

Growth factors are special proteins that tell cells when to divide, move, or repair tissue. Many of these, such as TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta) and PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor), attach to the ECM. By holding onto these molecules, the ECM creates concentration gradients—like little maps—that guide cells to do the right job in the right place.

💡How the ECM Boosts Healing Signals

The ECM doesn’t just store growth factors—it helps make their signals stronger.

Here’s how:

- Fibronectin, a protein in the ECM, can bind to growth factors like VEGF165.

- When this happens, it forms a molecular team that brings growth factor receptors and integrins (on the cell surface) close together.

- This clustering makes cells respond more strongly—even if only a small amount of growth factor is present.

In short, the ECM works like both a storage system and a signal booster, helping cells heal faster and more efficiently.

Fibroblasts and Myofibroblasts: The Builders of the Healing Process

Fibroblasts are like the construction workers of the body during wound healing. They are responsible for repairing damaged tissue and rebuilding the extracellular matrix (ECM).

As healing progresses, fibroblasts undergo an incredible transformation—they become myofibroblasts, a more specialized type of cell. These myofibroblasts develop α-smooth muscle actin inside their structure, which gives them the ability to contract and pull the wound together, much like tiny muscle cells.

Fibroblasts are like the construction workers of the body during wound healing. They are responsible for repairing damaged tissue and rebuilding the extracellular matrix (ECM).

As healing progresses, fibroblasts undergo an incredible transformation—they become myofibroblasts, a more specialized type of cell. These myofibroblasts develop α-smooth muscle actin inside their structure, which gives them the ability to contract and pull the wound together, much like tiny muscle cells.

💡How Myofibroblasts Help Close Wounds

Myofibroblasts are incredibly strong for their size. They create powerful, long-lasting contractions—measured in micronewtons—that can continue for hours. These contractions help bring the edges of a wound closer together and reduce strain on the fragile collagen fibers forming in the area.

At the same time, myofibroblasts work in a balanced way by:

- Producing new ECM components, like collagen, to strengthen the tissue

- Releasing enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to break down old or damaged ECM

This allows the body to remove temporary materials, like the early fibrin matrix, and replace them with a stronger, permanent, collagen-rich structure.

ECM Remodeling: How the Body Rebuilds Itself After Injury

After an injury, the extracellular matrix (ECM) doesn’t stay the same—it goes through an impressive transformation. This process, called ECM remodeling, is carefully programmed to clean up damage, rebuild tissue, and restore function. Here’s how the body does it:

1. Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs): Cleaning Up the Damage

The first step in healing is cleanup. This job is done by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)—enzymes that rely on zinc to function. These enzymes can break down almost all parts of the ECM. Their main roles include:

- Removing damaged tissue

- Creating space for new cells to move in

- Releasing growth factors that are trapped in the ECM

Important MMPs—like MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9—help skin cells (keratinocytes) move across the wound surface by loosening their attachments to the dermal matrix. This step is essential for new skin to form over the wound.

2. Collagen Turnover and Scar Formation

As healing continues, fibroblasts start producing collagen, the main building block of new tissue.

- Type III collagen is made first—it's softer and more flexible.

- Later, it’s replaced by type I collagen, which is stronger and more durable

However, if this process is not well controlled, too much or disorganized collagen can form. This leads to thick, uneven collagen bundles, which results in scarring instead of proper regeneration.

3. Hyaluronic Acid: The Moisture Magnet

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is one of the most important molecules for keeping tissue hydrated during healing. It can hold an incredible amount of water—just a quarter teaspoon of HA can bind about 1.5 gallons of water!

- Early in healing, HA levels are high, which helps cells move easily across the wound.

- As the wound matures, HA levels naturally decrease.

4. Elastin: Why Scars Feel Different from Skin

Elastin is the protein that allows skin to stretch and bounce back. But during wound healing, the body doesn’t produce enough elastin. As a result, scar tissue forms without a proper elastic fiber network—which is why scars feel tighter and less flexible than normal skin.

Elastin production also declines with age, making healing less efficient over time. Interestingly, fetal wounds heal without scars, and this happens during a time when elastin networks are still developing—showing just how important elastin is for perfect healing.

Clinical Applications and the Future of ECM Research

Thanks to scientific advances, what we know about the extracellular matrix (ECM) is now being used to create real medical treatments, especially for wounds that won’t heal easily. With millions of people suffering from chronic wounds, doctors and researchers are turning to ECM-based therapies for better, faster healing.

ECM in Treating Chronic Wounds

One of the most successful uses of ECM is in chronic wound care.

- Acellular dermal matrices (ADMs)—like Alloderm™, DermACELL™, and GraftJacket®—are widely used alternatives to skin grafts.

- These products are made from donated tissue that has been decellularized—meaning the original cells are removed, but the natural structure of the ECM remains.

- This preserved ECM acts like a natural scaffold, helping the body rebuild healthy tissue faster.

Studies show that wounds treated with ADMs heal more quickly than those treated with traditional methods.

Also, many ECM-based products include hyaluronic acid, which reduces bacteria growth by blocking bacterial hyaluronidase—helping wounds stay cleaner and infection-free.

Genetic Factors That Affect ECM and Healing

ECM function is controlled by over 100 genes. Mutations in these genes can lead to poor or abnormal healing.

- Changes in collagen genes (types I, III, IV, V, VI, VII, XIV, XVI, and XVII) can cause skin disorders and scarring problems.

- In mouse studies, animals with collagen III deficiency developed spontaneous skin wounds and uneven collagen fibers.

- Scientists are now studying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—tiny genetic variations—to understand why some people heal faster or scar less than others.

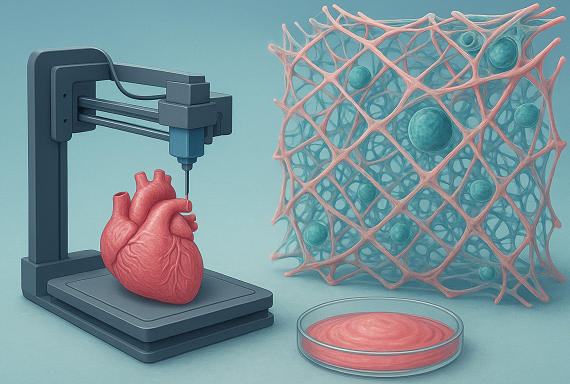

New and Emerging ECM-Based Therapies

The future of wound healing is moving toward smarter, more personalized materials inspired by the ECM.

Promising innovations include:

- Biomimetic materials – These are man-made materials designed to imitate the natural structure and chemistry of the ECM. Some even target integrin signaling pathways to improve how cells attach and respond.

- Oxygen-rich chitosan hydrogels – These gels can deliver antibiotics and oxygen at the same time. In diabetic wound models, they improved skin repair and function.

- In vitro-deposited ECM – Instead of harvesting ECM from donated tissues, scientists are growing cell-generated ECM in the lab, then integrating it into biomaterials for therapy.

Conclusion

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is like the body’s natural support system that helps tissues stay strong and heal when injured. It’s not just a structure—it also sends signals that guide cells on where to go, what to do, and when to start or stop healing.

During wound healing, the ECM and cells work together. Damaged parts are broken down, new proteins like collagen are built, and the wound slowly becomes stronger. Sometimes this process creates scars instead of perfect tissue.

Today, doctors use ECM-based materials, such as acellular dermal matrices, to help difficult wounds heal faster. Scientists are also designing new materials that mimic the ECM to improve tissue repair and reduce scarring.

As research continues, understanding the ECM will help create better treatments that support the body’s natural ability to repair itself.

.png)

.webp)

.webp)

.png)